Building a Budget-Friendly Lab VPS Platform – Part 2: Architecture

In Part 1, I talked about why I built this platform.

Not because I wanted to compete with hyperscalers — but because cloud KVM pricing simply doesn’t make sense when you want labs that stay up for weeks, evolve over time, and grow as your understanding grows, and purchasing baremetal servers has a larger upfront cost, and if you let it run 24/7 you will get hit with reaccuring charges as well (Electicity bill).

In this post, I want to get concrete.

This isn’t a theoretical architecture or a polished cloud-native diagram. This is the real system that provisions VMs, bills users, exposes access, and enforces limits — built using tools I intentionally chose because they’re open source, inspectable, and reusable by anyone else who wants to build something similar.

The Actual Shape of the System

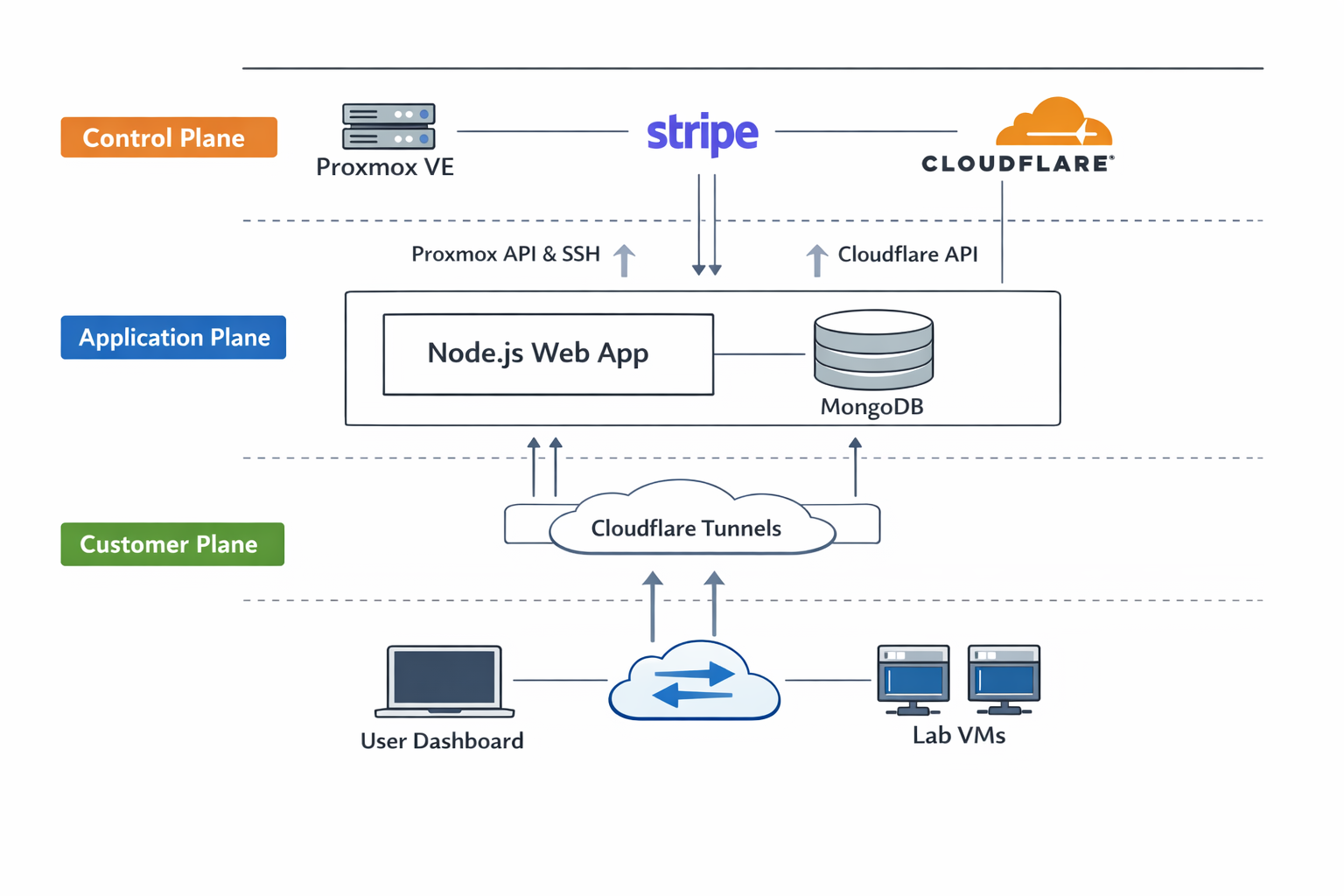

At a high level, the platform breaks cleanly into three planes:

- The control plane: Proxmox, Stripe, and Cloudflare

- The application plane: the Node.js orchestration app and MongoDB

- The customer plane: what users interact with — the dashboard and their lab VMs

Those planes are intentionally separated. That separation shows up everywhere in the code and in how access is enforced.

The web application itself runs inside Docker on a dedicated VM hosted on Proxmox. MongoDB runs alongside it using Docker Compose. This VM lives on its own VLAN, and a firewall acts as the default gateway and policy enforcement point for all lab-related traffic.

The application is allowed to talk to Proxmox.

Users never are.

Architecture Diagram

This diagram matches the system described in this post — no hand-waving, no imaginary services.

Why Proxmox Is the Foundation

Yes, Proxmox gives me real KVM virtualization. Yes, it handles templates, cloning, snapshots, and lifecycle management cleanly.

But the real reason I chose Proxmox is simpler: it’s open source.

I want a platform that can be understood, rebuilt, and extended by others. I don’t want a dependency on a vendor API that changes pricing or behavior overnight. If someone wants to take this code and run it on their own hardware, they should be able to.

In this design, Proxmox is treated strictly as an internal control plane. The application interacts with it in two ways:

- The Proxmox REST API for cloning, configuration changes, and lifecycle state

- SSH for operations for coping over cloud-init scripts to the snippets folder

That dual approach is intentional. Proxmox does not yet provide a way to copy cloud-init scripts via the API.

The Application Is an Orchestrator, Not a Platform

The Node.js application does a lot of things, but it has one responsibility: orchestration.

It does not try to be clever.

It does not trust browser actions.

It does not treat users as a source of truth.

What it does own is the sequencing of state transitions:

- Authentication and sessions

- Stripe checkout and subscription management

- VM provisioning only after payment confirmation

- Resize orchestration tied directly to billing events

- Cloudflare Tunnel creation and cleanup

- noVNC console brokering

- Enforcement when billing fails

That’s why the main server file is large. It isn’t intentional complexity — it’s the result of being a newbie to this and attempting to be explicit about every state change and every boundary.

Stripe Is the Source of Truth

One rule drives nearly every architectural decision in this system:

Nothing happens on Proxmox until Stripe confirms payment.

Not provisioning.

Not resizing.

Not restoring access.

When a user selects a plan and checks out, the app records intent. That record exists only to track progress.

The real commit point is the Stripe webhook.

When Stripe sends checkout.session.completed, only then does the application:

- Mark the order as paid

- Begin provisioning asynchronously

- Start cloning and configuring a VM

The browser redirect after checkout is cosmetic. The webhook is authoritative.

The same rule applies to resizes. Increasing CPU or RAM follows a strict sequence:

- Update the Stripe subscription

- Force Stripe to generate and attempt proration payment

- Wait for confirmation

- Shut down the VM

- Apply the new resources

- Restart

If payment fails or requires action, nothing changes on Proxmox. The VM stays exactly as it was.

Infrastructure never moves ahead of billing.

VM Provisioning: What Actually Happens

Once payment is confirmed, provisioning follows a deterministic path.

A new VMID is allocated by inspecting cluster state. No guessing. No randomness.

The app clones from a prebuilt template — either an EVE-NG CE image or a Containerlab image — depending on the plan selected. These templates already have the necessary software installed.

After cloning, the app waits for Proxmox to release its internal lock. This matters. Acting too early leads to inconsistent behavior.

Only after the lock clears does configuration begin:

- CPU cores and memory are applied

- Disk is resized if needed

- Cloud-init parameters are injected

- Networking is configured via DHCP

At this point, the VM still isn’t reachable. That’s intentional.

Cloudflare Tunnels Solve the Public IP Problem

I don’t have a pool of public IPv4 addresses. Even if I did, handing one to every lab VM would be expensive, unnecessary, and a security liability.

Instead, every VM gets a Cloudflare Tunnel.

The application uses the Cloudflare API to:

- Create a tunnel per VM

- Generate a hostname tied to the VMID

- Route SSH and optional web traffic through the tunnel

This keeps Proxmox and internal networks completely hidden while giving users instant access.

No public IPs.

No exposed hypervisors.

No per-VM firewall gymnastics.

Just tunnels.

Cloud-Init as the Handoff Point

Once the tunnel exists, the application renders a cloud-init configuration that injects:

- The Cloudflare tunnel token

- User credentials

- SSH configuration bound to the tunnel hostname

That cloud-init file is uploaded to Proxmox as a snippet and attached before first boot.

From that point on, the VM configures itself. The platform never needs to SSH into the guest to finish setup.

That boundary matters. The application controls lifecycle. The guest controls itself.

Console Access Without Proxmox Exposure

Users can open a noVNC console from the dashboard, but they never connect to Proxmox directly.

Instead, the application:

- Requests a short-lived VNC ticket from Proxmox

- Stores it briefly in the user’s session

- Proxies the WebSocket connection between the browser and Proxmox

Users never see node names, internal IPs, or cluster details. They see a console window and their VMID — nothing more.

That abstraction is deliberate.

Billing Enforcement Is Automatic

When Stripe sends an invoice.payment_failed event, the application immediately:

- Marks the VM as suspended

- Stops it on Proxmox

- Blocks console access

When payment succeeds again, the VM is restored automatically.

This isn’t punitive. It’s operational hygiene. Infrastructure that isn’t paid for shouldn’t keep running, and enforcement should never be manual.

What This Architecture Optimizes For

This platform is not a general-purpose cloud.

It’s optimized for:

- Long-running lab environments

- Predictable CPU and memory performance

- Minimal abstraction leakage

- Clear failure modes

- Honest economics

It’s built entirely on open tooling so others can reuse the ideas, borrow the code, or improve on it.

There are tradeoffs. Stripe webhooks are finicky. Proxmox has quirks. Cloudflare APIs aren’t always pleasant.

In the end, this is the kind of platform I wish had existed when I was working toward my CCIE — something affordable enough to leave running, flexible enough to evolve, and far less painful than investing heavily in bare-metal hardware that, once the exams were over, mostly ended up gathering dust.

What’s Next

In Part 3, I’ll dig into the VM templates themselves — how the EVE-NG and Containerlab images are built, what’s baked in, and what I intentionally leave out.

There’s also more to explore around scaling beyond a single node, adding stricter tenancy boundaries, and tightening operational safeguards as the platform grows.

This is just the platform as it exists today — shaped by real constraints, real tradeoffs, and the reality of running labs that don’t disappear after a weekend.